| Kurt Plinke, Artist and Naturalist |

Between the Waters

life, Art and The Nature of things Between the Atlantic and the Chesapeake

|

Sometimes the value of a thing does not correlate with the amount of money spent on that object. I have found this to be the case time and time again. Some of the things accumulated in my life that I really would never want to be apart from are not what have emptied my wallet. Paint brushes are often those kinds of things. The most expensive are usually not those that I find the most useful in the long run. And it seems that these particular brushes, the ones I have loved the most, when first seen showed their special nature right away. Like love at first sight, it's as though they were destined to be special. It's easy to spend an awful lot of money on a watercolor brush. The first good brush I owned, I bought at The Letter Shop in Lancaster, Ohio, in the early 70's. I had just enrolled in a watercolor class taught by LeLand McClellan at the local YMCA. On his supply list for the class, he suggested a Winsor Newton series 7 # 8 round brush. I remember it well, not only because it had a gleaming black handle and beautiful polished nickel ferrule, but also because it was so expensive. I can still recall the price... $33.00. Back in the day, that was a load of money. And I have to say, it was a really nice brush. Hand-made in England, Winsor Newton series 7 brushes are arguably the best watercolor brushes that can be bought. A brush like it today sells for well over a $100. It's strange though... I don't consider that long-gone brush to be one of my favorites. And what is stranger... None of my truly favorites cost anywhere close to that much. Probably my all-time favorite brush is an old beater one inch flat I bought when I was in college. A blue-handled student-grade Grumbacher, I purchased it for five dollars at the Bowling Green State University book store in 1977. I've used that brush ever since, softly washing watery backgrounds on many hundreds of sheets of Arches, Waterford and Winsor Newton paper. The supple snappiness of the long nylon bristles are always predictable, leaving a smooth as satin sheet of water in its wake. Each time I reach for that battered blue handle, I know what I'll get... a lovely layer of clean wash. About ten years ago, the pewter-toned ferrule wiggled it's way loose from the handle. If it had been a lesser brush, I would have tossed it, using the handle to mark a garden bed. But I loved this brush, and even in two pieces, I couldn't bring myself to discard it. Instead, I wrapped a couple of turns of masking tape over the end of the battered stick, and twisted the ferrule back into place. Amazingly, since then I have only had to replace the tape once. Another flat, this time a two-inch Robert Simmons with a burnt sienna-toned handle, is my other favorite always faithful wash brush. I found this one on sale in a huge cardboard box of close-out brushes in the back of the Ben Franklin craft store in Easton, Maryland. The box was about as big as a washing machine, and I dug through it one day about fifteen years ago. The handwritten sign on the box said, "all brushes, 2.99." When I saw that sign, it felt like Christmas. I found about twenty brushes in there that were spectacular. This big flat was the best of them. Most of the others, approaching an equal caliber, I gave as gifts to artists I knew would appreciate them.

I think I like this particular flat so well partly because it was such a great deal, and partly the way the leading edge of the bristles are cut. Usually a flat is cut cleanly, leaving an edge like a knife. This one, though, is just a tiny bit ragged. It was that way when I found it. That ragged edge, when half-loaded with pigment and dragged lightly across a page, leaves the most amazing textural trail behind it. Those subtle little streaks add so much interest to a painting and really can bring unity to an entire composition as they can be faintly found across a painting. A good flat brush is something special. I must say have had some very expensive round brushes, but none of them matched the black-handled Robert Simmons long #12 that I also found that day in the close-out bin at Ben Franklin. My first Winsor Newton Series 7 #8 Kolinsky Sable brush perhaps came close to being as good as this old reliable Robert Simmons. Over the years, the tooth of every piece of cold-press paper has taken its toll, and the fine tip on the old RS brush is long worn away. Even so, all of the part-sable hairs on this brush remain flexible and wonderfully adept at going where they should with a tiny wrist flick or roll. I love that round. And it was only $2.99 on close-out. I don't even remember how I came into possession of another of my favorites; a small stick-handled French quill brush with what I assume is squirrel hair that makes up the head of the thin little detailer. I like it because it was a surprise to find, and because the soft barrel holds a ton of paint, while still allowing a hair's-width line to flow from the tip. The handle could perhaps have been a little thicker for my pork-chop hands, but the rough natural feel of the stick/handle in my hands make up for the narrowness. Plus, the tip, held in place by a goose quill and twisted copper wire looks awesomely cool. Another "brush" I reach for all the time is actually one of many like it that I made myself. A chop-stick handle on each, trimmed bits of sea sponge were affixed to the former eating utensils with waxed fly-tying line. Technically, I suppose these are not brushes, not having any hair. But they are wonderful mark-makers. Dragged across a surface, they leave very un-brushy smudges, perfect when painting a fallow field or autumn tree line. I should probably make lots more, patent and market them. My other two favorites are liner brushes. One is longer than the other, with a slightly thicker barrel. Both, because of the length of their flexible heads, hold a lot of liquid, making them great for tiny technical marks. Weirdly, I also use them a lot for drybrush and scumbling, dragging them side-while across rough paper, The smaller of the two, a Robert Simmons Expressions #2, is probably my smallest brush, and unlike the the French quill brush, has a huge fat handle. I love grabbing for that brush, because I know it will never fly loose and add streaks of paint where I did not intend on an almost-finished piece. It's not just the easy to hold ball bat handle that I like, though. While the turquoise-green handle is massive, the head is delicate. I've found that if I load this petite little package of hairs just right, I can paint miniature rat whiskers by the dozen without having to re-load. I'm not sure why I would ever need dozens of miniature rat whiskers painted, nut it's nice to know that I could, if the need ever arose. At least as long as I have that little # 2 liner with the giant handle. There are other brushes I love... maybe almost as much. A 3/4" filbert rake I bought at a decoy carver's show years ago quickly comes to mind, as does a cat's tongue detailing brush that I often seem to reach for when I need variable-width lines. If I thought about it, I could name more. But even though I have hundreds of brushes, each with a minor tale to tell, the seven, with their minor little stories, are destined to always be my favorites.

0 Comments

A Little Brown Bird in the Weeds... the subject of January's watercolor workshop at Sewell Mills.In the tangle of brush, trees and vines between the studio and the river the small brown birds have made themselves at home again for the winter. White-throated Sparrows, Juncos, Fox Sparrows, Tree Sparrows, Field Sparrows, Swamp Sparrows, Chipping Sparrows and Song Sparrows all compete to see who can make the most commotion as they rustle through dry leaves, looking for seeds and small cold insects. I look for them as the leaves drop, but now that Winter is here and the cold nights drive us indoors, little packs of sparrows become more and more noticeable.  Of these little brown bundles of sparrow energy, I think my favorite is the Song Sparrow. This dapper little bird is gorgeous shades of burnt sienna, sepia and gray. His white breast and flanks are heavily streaked with dark jagged lines, forming a dark blot on the middle of his breast. His cap is a mix of reddish-brown and gray, and his face sports a distinctive set of light and dark stripes. Song Sparrows were not named for their jaunty little set of feathers, however. The name, Song Sparrow, is more reflective of their distinctive call, a warbling series of variable notes that almost always begin with a few regularly-spaced single notes.  Song sparrows are not like many other sparrows, who only visit the Eastern Shore during the cold winter months. Song Sparrows call the shore home year-round, and I often find their nests in brushy areas along the edges of farm fields across the county. Usually I notice their nests after the leaves have fallen and the landscapes turn gray and brown, like the Song Sparrows themselves. Their nests are mainly woven grasses, loosely constructed and about nose high off the ground in a twiggy joining of small branches. At the feeders, Song Sparrows are not the most numerous of little birds. White-throats and Juncos outnumber Song Sparrows at least ten to one. This makes me like Song Sparrows even more. Usually one or two of them will show up at the feeders at any one time. Active, these little streaked birds stand out among the other ground birds, who generally tend to move more deliberately. These are the birds we'll be painting during our January watercolor workshop at the studio. We won't be painting a feeder or a tangled bunch of grasses, just a simple study of a Song Sparrow tightly gripping an interesting Winter seed head. If you've never painted a small bird with watercolors, this workshop would be a great place to start. The markings on this little guy will add just enough challenge to keep anyone interested, but the painting will be simple enough to make success all but guaranteed. If you'd like to sign up for this workshop, check out the workshops and classes page of this website. But attend the workshop or not, look for Song Sparrows every time you hear the leaves rustle this time of year. CONSIDERING WHY I PAINT AND WHAT I PAINT

FOR YEARS, I CONSIDERED MYSELF A WILDLIFE ARTIST. And really, that was what I was... a person who painted birds, and occasionally other wild creatures. I liked doing that. It was what interested me, what surrounded me and what, really, I lived. Over the past few years, however, I kept finding myself drifting away from just painting wildlife. A landscape, an abstract, even an occasional portrait crept onto a piece of watercolor paper in my studio. But these seemed to be no more than brief passing fancies. For a short time, I considered abandoning watercolors and moving completely to a different medium for the majority of my work. I was restless. Always a bit (or more than a bit) on the ADD continuum, I supposed I just quickly lost interest and was looking to snag the flittering butterfly outside the window. I mean, I was just grasping at random thoughts and images. If it was something I saw or was intrigued by, I painted it. Or at least I considered how I would paint it. There was no real rhyme nor reason... just a series of semi-unrelated images flowing from brushes in my studio. Some I liked, and will probably paint more similar to them in the future. Others I have never even showed anyone, and probably never will. They were experiments. Each time I branched out and painted using new techniques, new subjects or new colors, I felt as though I were looking for more than just a set of paintings, I was looking for a new theme. It seems as though over the past months, I may have finally settled upon a theme for my work, besides just painting birds. But before I put a name to it, I need to explain a little. First, a theme is an underlying idea or message in a painting or a body of paintings. My theme has always been sort of The Wonder Of Wildlife. I say sort of, because really my paintings have always been almost illustrations in most cases. I once had a professor tell me that I was not an artist, I was an illustrator. I argued with him at the time, and still disagree, that illustration is Art. But that is not the point. My paintings were essentially illustrations of various species in their natural surroundings. And I am not saying that these do not have worth. I am saying that the theme of all of these paintings make up a group of works that I need to expand beyond; that I need to move in a direction with what I paint which has more personal meaning. That was why I started painting landscapes, abstracts and experimenting with different mediums. I wanted to paint something with deeper meaning and I did not know where to go with that desire. For a while, I essentially stopped painting. I was at an end of having something to paint about. As I considered what to paint, almost purely by chance, I began occasionally hanging out at a couple of places near to the studio. These were places like an old dairy beside the school where I teach. The dairy no longer functions as a local dairy, and may soon see perk test tubes in the fields surrounding the old barns and few remaining cows. Another is a swatch of land, barns and people who have become collectors of unusual hobbies. Here, falconing and small plot farming are the norm. Still another is the entire town of Greensboro, the town near where I live. All three of these places have something in common, and have lead me to a theme. All three places are grounded in the past, and struggling with a future full of change. The dairy is passing into history... a sad way to deal with change. Opposed to that, the land and people nearby have formed their own little island, a place to insulate themselves from change, to preserve old things and old ways of doing. Greensboro (like every small rural town) itself is in ways embracing the change, and in ways grasping at a past that is fading. And that, I recently realized, is what I want to paint... the changing history around the Eastern Shore that is happening right now. This is a theme that I feel has enough import to hold my attention, and can be expressed in a number of ways. Sometimes I am disheartened as I see our past falling away, like the roof of an old abandoned farm building as it collapses. I can paint those feelings. Sometimes I love how some things are constant throughout the passing of time, like decoys in the back of a truck or a bucket of fish freshly caught along the river. I know that these things, too, are changing. It seems that every year, fewer people spend a spring day fishing, or a cold wet morning in a duck blind. And it saddens me that these things may fade. As the Eastern Shore and it's people transform from an insulated group of rugged souls dependent upon the land and waters, it is inevitable that the place must change. So in the end, I have come to a point where I am to be a historian, documenting the slow grinding of the wheel, the change from one way of life to another. My paintings, full of the things that satisfy artists, such as composition and movement and repetition, also are a sort of illustration... a documentation of the story of our times here in Maryland. Our Eastern Shore... a place where change has traditionally happened slowly, is beginning to catch up with those on the other side of the bay. Reluctantly, we are slowly modernizing. And in this modernization, this accelerated and sometimes unwanted change, there are poignant stories. My paintings are beginning to document these changes, these stories of people and place.  This does not mean I will abandon wildlife. The small things in nature that surround us here on the eastern shore still have fascinations for me, and still have stories to tell. I suspect that these paintings may include more and more of the interactions between the natural world and the changing human practices that are emerging or fading. After all, we still live on the land here, and we all still, in some ways, are connected to the natural eastern shore that continues around us. If you want to see some of these stories of change, memories and growth of ourselves, of our homes, come to Summerfest in Denton in mid August. I'll have a collection of these stories there.  Photo Credit: Carnegie Museum of Natural History Photo Credit: Carnegie Museum of Natural History Sometimes, I look out the window and swear that I see dinosaurs in the garden. Not Triceratops or T-rex or anything. Just common, everyday dinosaurs. Smallish (for a dinosaur), dark, long-legged and primitive. When I was a kid, the idea of dinosaurs in the woods behind the barn always lurked in the back of my mind. I could clamp my eyes shut, focus my thoughts and there they would be... not big scary dinosaurs, but gentle creatures, almost like pet dinosaurs, hiding behind the big burr oak trees on the hill. Still wild, mind you, but not the dangerous kind of wild. At least, that's how I imagined modern dinosaurs; huge, gentle creatures with long necks and long legs. As a child, I grew up in several parts of the country. But most of my clearest memories from my younger years were on a farm in southern Wisconsin. I had great friends there, and we roamed and played across the woods and fields near Whitewater Lake. Mostly we pretended to be soldiers, or cowboys, or explorers. We dug caves out of the hillsides, built cabins from old fallen tree branches and chased long-gone deer by following their tracks in the snow. But when my friends were not around, I dreamed of dinosaurs. I wanted to be a scientist when I grew up, just so I could somehow bring dinosaurs back, to be able to really see one. Occasionally I would find a small fossil in the rocks on the moraine hills behind our big barn. These excited me to find more. On a trip to the Milwaukee Museum of Natural History I saw huge fossilized dinosaur bones and entire skeletons, held together with wires, bronze-brown and ancient looking. These were even more amazing to me as I imagined unearthing entire skeletal creatures from ancient bedrock and then painstakingly reassembling them. But old fossils were not enough. I wanted to see them in the flesh, walking around, doing what dinosaurs do. I hoped that someday I would discover a way to recreate these big beasts and give them a chance to live again. As I got older, those thoughts faded and I became more interested in the living things that surround us all... the birds, mammals and other creatures. When that movie about the dinosaur park came out and then the sequels, I was instantly returned to those dreams, however. The idea of real-life dinosaurs roaming the countryside again sprang up in my head, and I discovered that the notion of recreating dinosaurs still hides in a mind corner of mine. And then, once in a while I actually, really, truly see one; strolling across my yard, under the fruit trees, in the garden, or peaking from the underbrush at me. The round, scowling little bead of an eye, the long sinuous neck, the primitive walk all tell me I am looking at a dinosaur. I saw one this morning, first slowly strolling across the front lawn. Then she reappeared beneath an apple tree, looking for insects in the shaded meadow grasses of the orchard.

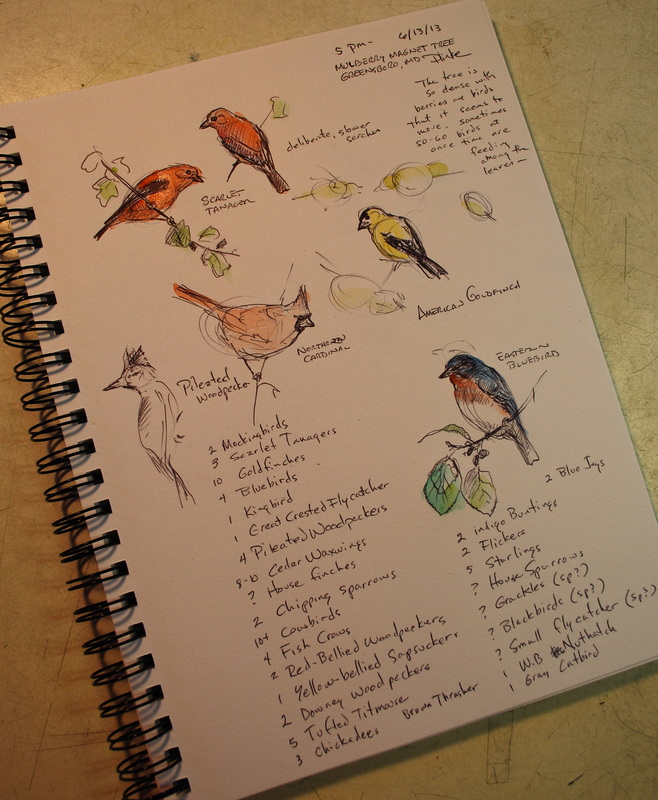

easily wend their way through blackberry brambles, greenbriers and other dense undergrowth. I have come upon turkeys along a path, and not seen them among the dense path-side thickets until I am almost on top of them. Turkeys, in fact, are very similar to dinosaurs. Bot the wild turkey and the Tyrannosaurus Rex share a furcula, a special bone that most other creatures do not have. (http://www.livescience.com/32228-what-do-turkeys-and-t-rex-have-in-common.html) A furcula is a wish-bone. In fact, it is a fusion of the collar bone and the sternum. Velociraptors also had a furcula. The turkey that ambled through the back yard today, however, did not look so much like a velociraptor as it did some other small dinosaurs. Animals like the dinosaur called Anzul, pictured in the photo of the skeleton above, probably looked a lot like turkeys in many ways. In fact, scientists now believe that dinosaurs like the Anzul and even velociraptors wore feathery coats.  It may be that turkeys, ambling through the woods behind the house, are as close as I'll ever get to seeing a real live dinosaur. That's probably good. I'll just keep imagining that they are dinosaurs, living relicts from eons past, stalking across the primeval Maryland landscape.  It is Christmas morning, and the weather is warm here in Greensboro. At almost sixty degrees outside, the air is practically balmy for a late December day on Maryland's eastern shore. A few days ago we were thinking it might snow as we gathered around the wood stove to stay warm. Then the wind shifted, the rain fell for days (thanks that it was rain and not snow), and now we are enjoying a windy, spring-feeling day. It almost doesn't seem like Christmas. Looking through the window this morning, I saw seven bluebirds, perched all in a row along the picket fence out back. The damp gray wood was a suitable match for the blues, pale grays and reds of these striking little birds. As I stepped out the back door to try to photograph the perfect little line of brightly colored birds, they scattered, flashing cerulean and sapphire. Their glittering wings lifting them all to various points on nearby bare branches. Even their calls reminded me less of Christmas and more of Spring, when their song can be heard almost continuously while they check out the local nesting boxes for suitable sites. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Maryland is about as far north as bluebirds will regularly spend the winter. Any farther north and they migrate south as the winds begin to howl. Even so, I feel as though I don't usually notice as many bluebirds in the winter as I do on warm summer days. During the warmer times of the year, bluebirds mainly eat berries and insects. Winter fare includes berries of holly, mistletoe and juniper, as well as rose hips. They will occasionally come to the feeders, if we put out raisins or other dried small bits of fruit. Bluebirds are members of the thrush family. This group of birds includes not only bluebirds, but robins, the veery and wood thrushes. Most of these birds are thought of as Summer birds, but many quietly spend all year poking about, looking for food in Maryland. The American Robin, often thought of as a signal that Spring has arrived, like the bluebird actually spends the Winter here as well. It was certainly a treat seeing the long line of little blue bodies on the fence this morning.  Eventually, Winter will arrive here, and we begin to think about how best to portray in paint, that which is howling outside the doors of the studio. That is why I've chosen our next watercolor workshop (scheduled for January 24th) here at the studio to be another small year-round resident; a Winter Wren. As fluffy as they are, with their muted, mottled tones of brown, they are the perfect "winter feel" bird. We'll be painting this one on the remains of a goldenrod, including a gall on the stem of the plant. Galls are swollen sections of a plant, grown to surround a larvae of an insect, the Goldenrod Gall Fly. I remember these galls from when I was a child in Wisconsin. Back then Tony, Frank, Matt and I would collect goldenrod galls before going ice fishing. Inside each of the brown galls was a juicy fly larvae... perfect bait for catching bluegills, crappies and perch through a hole cut in the ice. Those are great memories, brought back every time I tramp through an untilled field in winter. I happen upon a gall on a stem, and I am once again back on the lake, using an iron bar to cut a hole through to clear water, then jigging for panfish with my friends from the next farm. My mother always made anise cookies close to Christmas. I would always head to the lake carrying not only galls, but a pocket full of her wonderful homemade treats. ...and that feels like Christmas.  Recently, my wife mentioned that she had been seeing more and more bald eagles near the studio. At the time, I realized that I had also noticed an increase in eagle sightings. I told her I thought that it was probably the result of a combination of factors. One factor is the recent harvesting of crops in the fields near the studio. Bald eagles often scavenge, and a lot of tractor activity in a field leaves remains in its wake. Tractors run over mice, rabbits and other animals in the fields, and eagles will find them. Also, with no tall corn or bean plants standing, it is easier to see eagles and other scavengers as they congregate around a food source in the middle of a cut field. Along the same vain, as deer-hunting season gets into full swing, there are inevitable lost shots. Some deer, wounded by hunters, manage to topple where the hunter is unable to find them. Eagles, however, seem to be able to locate this bounty with ease. Along with vultures, eagles will mass around a deer carcass lying in a field. On my way to Dover last week, I saw seven eagles and uncountable turkey vultures congregated around a lost deer carcass. Eagles also are much easier to see as trees drop their leaves. Perched high in a gum tree along the river, an eagle would be invisible before the tree dropped its covering blanket of foliage. I have noticed, as well, that I have seen quite a few eagle pairs in recent weeks. Eagles begin to nest in mid-winter. It is possible that in this area, we are seeing the beginning of pair bonding activities. As eagles begin to locate their mates, or find new ones, they are much more active. Flying in pairs, they wheel about overhead. It always amazes me how such a big bird can be so agile in the skies. As the light hits them, adult eagles are amazingly easy to identify, their white head and tail glowing in contrast to their dark bodies. It may be that eagle numbers in general are also on the rise. It was not long ago that bald eagles were considered an endangered species. According to the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the number of active nesting sites in Maryland had grown from a low of 39 nests in 1997 to 368 nest in 2004, the last year the study noted. As a part of that same series of reports, the number of wintering bald eagles increased in a similar manner. During the 1979 Wintering eagle survey, 44 bald eagles were noted. In 2008, that number had risen to 303 birds. That is an amazing increase. Whatever the reason, my wife is right. Eagles do seem to be everywhere. If you haven’t noticed, look around as you travel from place to place. If you look, I’ll bet that you will see large numbers of our national symbol all around you… flying over Easton town square, cruising low over a Dorchester field edge, massed in the middle of a newly plowed field near Chestertown, or just sitting like a sentinel on the bare branch of a tree.  OTHER NEWS: If you had not noticed, we’ve revamped Sewell Mills Studio & Gallery’s website, adding a lot of new content, features and an online store where paintings, prints and cards may be ordered. Take a moment and wander through… NEW WORKSHOPS SCHEDULED: A new series of workshops have also been scheduled in the studio. The first new workshop is set for Saturday, January 24th. We’ll be painting a Winter Wren on a goldenrod gall. It should be good... consider reserving a chair and attending. Christmas is coming soon…  Pileated Woodpeckers visited regularly. Pileated Woodpeckers visited regularly. First, I wanted to remind you about a couple of workshops at the studio this week. We'll be painting a plein aire scene on Wednesday, and then on this coming Saturday, we will create a small painting of several baby wood ducks on a nesting box. Both should be fun and informative. check the Shows and Workshops page on my website for more information. In an earlier post, I wrote about a tree in the back yard near our studio. It is a Mulberry Tree which stands alone over a section of the parking lot. Every June, the tree fills with berries, and attracts birds like a magnet. The berries have just about disappeared, and I wanted to post a final visitor's tally for this incredible tree. This list is a compilation of species that were seen visiting this tree from June first to July first, 2013. I think you'll agree that this Mulberry Tree is truly a special tree when it comes to it's ability to attract birds. (gray squirrels also frequented the tree) This list includes species' common names, and does not reflect numbers of individual birds of any one species.

I think you will agree that a lot of birds were attracted to this tree over the month of June. From my notes, at least forty species of birds used this one tree ove the course of thirty days. The list would be more impressive if I could include numbers of individual species, but it was impossible to determine how many different individuals visited. I know that there were at least six different Pileated Woodpeckers visiting the tree, because I saw that many at one time. Likewise, four Scarlet Tanagers, Two Baltimore Orioles, and five Red-bellied Woodpeckers. One of the most interesting observations I made involved both the Great Crested Flycatcher and Kingbirds. I had always assumed that these birds were entirely insectivores. What I saw this past month, however, is that both species of flycatchers eat a considerable amount of fruit. The Great Crested Flycatcher, especially, gorged on berries frequently. I plan to watch this tree again next year. Perhaps we can add to the list. If you have a magnet tree or shrub, or even a water feature in your garden that attracts varied species, think about keeping a list. It could be fun.  We have an Aucuba in our back yard, a handsome speckled shrub. Standing about six feet tall, this particular Aucuba, or Spotted Laurel, has begun to encroach upon the path leading to a gated garden. As my wife and I looked at how to cut it back, she noticed a nest in the shrub, about four feet off of the ground. (she always spots that sort of thing before I do) There were eggs in it, so trimming the shrub was set on hold. I put the loppers away, and we went to examine the nest more closely. I could tell from the shape of the nest that it was made by a house finch. I had seen many of these nests in our yard... the house finch, with it's raspberry-colored head, is one of the more common birds near the house. We peeked into the nest, and saw that there were two pale, almost-white eggs in the nest, and two eggs, dotted with brown flecks. A third pale egg was wedged into a branch just below the nest. I hate when I see this in a nest. I shouldn't, but I do. I knew right away that one of the Cowbirds we see at the feeders had been there, and had laid several eggs in the House Finch's nest. The Cowbird had also probably pushed the one finch egg out of the nest, as well. I get mad when I see this, because Cowbirds do this to so many native songbirds. There are some species of birds that are seriously parasitized by Cowbirds. That's why I get mad. It doesn't seem fair. On the other hand, Cowbirds are also a native songbird. They even actually have a pretty song, sort of a liquid tumbling song. If they weren't such parasites, they'de be pretty.  Brown-headed Cowbirds, Molothrus ater, are, as I said earlier, native to North America. They frequent open land, and their range has spread from the prairies as we have cleared land and made the eastern United States more open. Cowbirds are a species of blackbird, relatively small, but stocky, with a large head. The brown-headed Cowbird male is dark, nearly black, with a brownish head and nape. The female is lighter, resembling a large House Sparrow, light tan and brown, sometimes with very pale streaks on the back. It is the female Cowbird that waits to place her eggs in the nests of other birds. According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, All About Birds, (http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/brown-headed_cowbird/id), different Cowbird females tend to lay eggs in only one species of bird. Some might chose a Yellow Warbler, while the one in my back yard choses to lay eggs in the nests of House Finches. Not all Cowbirds are so choosy, it appears that a few will lay their eggs in almost any nest. Sometimes, the female Cowbird pushes the nesting species' eggs out of the nest as she replaces them with her own. Other times, the young cowbird, which hatches quickly, pushes the other eggs out. In either case, the result is that the single remaining young is a Cowbird. The nesting birds feed the young cowbird as though it is their own. The female Cowbird is long-gone, and does not have any association with her young. Seeing small songbird, like a Yellowthroat or Chipping Sparrow raising a baby bird that is twice the size of the "parents" can seem almost comical, even though it is, at the same time, sad. Some species, such as the Kirkland's Warbler, are so seriously effected by Cowbirds, that they are endangered. Some birds, like the Yellow Warbler, differentiate between the eggs, and build a new nest on top of their old one, trapping the cowbird eggs deep beneath the new nest. Yellow Warbler nests sometimes are a stack of nests, one on top of the other, each containing cowbird eggs that will never hatch. House finches seem to be among the large group of birds that raise the cowbird young as their own, although I have discovered several cowbird eggs under the finch nest since first finding this particular nesting site. It may be that the female House Finch pushed out the uninvited eggs. According to Cornell, Cowbirds sometimes return to the nest, and finding their eggs gone, destroy the nest altogether. Despite the risk to the nest by an angry Cowbird, I want to intervene. I want to remove the cowbird eggs myself, helping out the finch family in my yard. So far I am refraining, allowing nature to take it's course. It will be interesting to see what happens.  my magnet tree. my magnet tree. What the heck is a Magnet Tree? I have one in my yard. It's a red mulberry tree that attracts birds by the score this time of year. Early in the morning, just after sunrise, there doesn't seem to be a twig on the entire tree that isn't dripping with birds. Mulberries, plump and ripe, hang in clumps from every branch. As I walk past the tree on the way to my truck, I must walk through a dense carpet of berries that cover the ground. Fermenting among the grass, it reminds me of young wine. Not good wine, but still... Not all magnet trees are mulberries. Some are nut trees, or maple trees, or any other tree that bears fruit. I've never heard anyone else call these special trees magnet trees, but the name fits. These lone trees seem to draw birds from all over as they feast on the bounty of the magnet tree.  My magnet tree stands by itself, but not far from a dense wood. As soon as the snow melts every year, I begin thinking about my tree. I watch as the leaves unfurl, and then as the fruit begins to form. Each berry starts as a hard white little mass. Beginning in late May, the berries begin to swell and turn first pale green, then red before becoming succulent, ripe purple fruit. This particular mulberry tree hangs over our parking lot, and stands about forty-five feet tall. As I pull my truck under the tree in spring, I know that soon I won't be able to park there. As the berries ripen, they fall like rain from the canopy, leaving large purple stains anywhere they land. I don't mind losing my parking lot each June, though. Because as the berries ripen, the birds arrive. First a woodpecker or two, then a lone robin appears. Within days, the tree is a cacophony of sound. Flapping wings, warning calls and chirps of delight fill the air. Behind it all, the sound of berries falling to the ground is a constant, like rain dripping from a roof on a dewy morning. After a few days, the buzzing of all sorts of insects also join the bird sounds. Bumble bees, wasps, yellow jackets, hornets and all sorts of buzzing creatures are attracted to the fallen fruit. Butterflies by the scores flutter about the branches, sipping sweetness from the ripening bounty. My main interest, though, is always the birds. I sit outside the studio, drawing them quickly as they land, gorge on berries, then fling themselves heavily into the sky. Sometimes, they eat too many over-ripe fruit. Then they tilt crazily, sitting sideways on the ground, looking like little feathered winos who've gulped too much from a paper bag. My favorite birds among the many visitors are the bright birds of summer... orioles, tanagers and goldfinches. We get both Baltimore Orioles and Orchard Orioles visiting the tree. Sometimes, there may be a dozen orioles in the tree at one time. Often, half a dozen tanagers can be seen at once near the tip-top of the tree. The bright flashes of screaming red and black startle my eye as the male tanagers move deliberately among the leaves. Pileated woodpeckers are among the flashiest birds that vist the tree. We are lucky enough to have three pairs nest nearby, and at times, six of the big birds are in the tree at one time, chasing each other with wide, flashing wingbeats. Sometimes, there are up to five species of woodpeckers in the tree at once. Along with the big pileateds, we have regular visits from red-bellies, downey and hairy woodpeckers as well as yellow-bellied sapsuckers. I love my magnet tree. I wait for it to fruit every year, looking forward to the myriad of species that it draws to my yard. I hope you can find your own magnet tree, and enjoy it as much as I do mine.  Cranefly Orchid, Tiliparia discolor, Winter foliage, 3/10/2013 Spring begins along the Choptank River with little spots of green, before the riotous outbreak that will shortly fill the bottom lands with color. I explored the leaf litter on Sunday, looking for some of those quiet green splashes. I found a few, including the leaves of Cranefly Orchids, laying flat against last fall's fallen leaves. Green above, a deep reddish-purple beneath, these leaves will soon disappear, replaced in late summer with foot-tall spikes, topped with a spiral of small flowers. We have several orchids in the woods along the river, but I think that the Cranefly Orchid is my favorite. Not as showy as Lady's Slippers, not as plentiful as Puttyroot Orchids, the Cranefly rewards those who look for it with delicate flowers atop a purple stem. The violet-white flowers are pretty, and resemble small insects in flight to me. Another plant that can be seen early in Spring is Ebony Spleenwort. In the sandy soil on slopes leading to the river, these small ferns can be found year-round, although at this time of the year only the sterile fronds, set in a whorl near the ground, can be seen. Before any other ferns have even sent up their first fiddleheads, Spleenworts are already there, preparing to unfurl their own fertile fronds as the days warm. I love the rich reddish-brown rachis on this little fern, shining up from among the leaf litter.  Sterile fronds of Ebony Spleenwort, Asplenium platyneuron. 3/10/2013 These little victories over the waning winter drabness make walks along the water more and more fun as spring begins here on the Eastern Shore. At the same time, a number of creatures become more active, and several species begin annual migrations to the Choptank. While I couldn't get a camera focused on any, several hermit thrushes perched briefly overhead as I walked the woods on Sunday. A gray fox ran off as I first headed down the path towards the river, and as I approached the river below the spillway, an otter splashed into the water. Red-shouldered hawks called overhead as I looked for the beginnings of Spring Beauties, which have not yet begun to poke through the bare soil near the river. Mourning Cloak butterflies flitted among the bare branches overhead as I caught the first Yellow Perch of spring on Sunday, a nice little 10" male, brightly colored. Soon the river will be full of perch, herring, shad and rockfish. Eagles, osprey and herons will fish the river, as will dozens of fishermen, all looking to snare as many of these fish as they can while they are in the shallows to breed. This is a great time of the year. |

What's News?Kurt Plinke: About Life, Art and the Nature of Things on the Eastern ShoreI write about things I've noticed, places I've been, plans I've made and paintings I've finished or am thinking about. Archives

February 2020

See recent naturalist observations I have posted on iNaturalist:

|

|

Sewell Mills Studio & Gallery

14210 Draper's Mill Road Greensboro, MD 21639 (410) 200-1743 [email protected] |

Rights to all images on this website, created by Kurt Plinke, remain the property of Kurt Plinke. Copying or use of these images is permissible only following written permission from Kurt Plinke. To use images for any purpose, contact [email protected] for permission.